Lara Weiss, Daniel Soliman and their team write a Digging diary every week (see below photos)

Excavations in Saqqara 2022

In mid-September, a research team from the National Museum of Antiquities arrived in Egypt, towards the village of Sakkara. This is where the excavation site is located, where they conduct six weeks of research into an ancient Egyptian burial field every year. After a two-year absence due to corona measures and the associated travel restrictions, the team will continue this year to excavate a new tomb, the entrance of which was found in 2019.

Team of specialists

As then, in addition to the archaeologists, a large team of specialists will go to Egypt, such as the Milanese surveyors, who carry out scans to document the ongoing excavations, a textile restorer from the Museo Egizio and specialists for researching human remains and pottery. Together with the project partners of the Turin Museo Egizio, the team hopes for beautiful and interesting finds.

Partner Museo Egizio

The team consists of several scientists and is led by Dr. habil. Lara Weiss and Dr. Daniel Soliman (curators of the Egyptian and Nubian collection of the National Museum of Antiquities), together with Dr. Christian Greco, director of the Museo Egizio, Turin. The project is co-funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research.

- Read more about the backgound and history of the excavation project in Saqqara.

Week 7, 2022: Antar Shadouf showing us photos of his family members who came from Quft and worked with archaeological missions in Saqqara (photo: Servaas Neijens)

Week7: Interviews on site with Essam Said Ahmed and Rafaat Abdel Karim, two important workmen of the Leiden-Turin mission (photo: Servaas Neijens)

Digging diary

Week 7 (21-28 October 2022): Egyptian workmen

By Fatma Keshk and Ashraquet Bastawrous

On the 15th of October, we (Fatma and Ashraquet) started the fieldwork of our research project that aims to study the contribution of Egyptian workmen in archaeology on the occasion of celebrating the 50th anniversary of the mission. Our work on this project is a little dream of ours coming true. In May 2020, we launched a campaign entitled Hands that excavated a civilization by Ashraquet Bastawrous on our page The Place and the People, where we aimed to shed light on the legacy of the Egyptian workmen in archaeological excavations through a holistic approach. Here in Saqqara, we have the wonderful opportunity to take our work to a deeper level of research while connecting it to the history of the Leiden-Turin expedition and its significant work through its long history since 1975.

Our project’s methodology relies on the study and documentation of all possible resources including library and archival research on the one hand and interviews on the other hand. The review of previous research on the legacy of Egyptian workmen at archaeological excavations has been keenly taken into consideration.

We hence started a fantastic journey of research through interviews that began with the raises (foreman) of the mission in the current season Hossam Azzam as well as workmen Raafat Abdel Karim, Mohamed Ragab, Youssef Hammady and many others. Our interviews began with our rais Hossam Azzam who generously introduced us to all the details of the daily work of the workmen at the archaeological site.

In addition to interviews; our research has extended to research trips around the village of Saqqara in order to reconstruct the social context of the workmen’s daily lives. Wandering around the streets of Saqqara village created nice coincidences, for example, seeing raises Ibrahim Abdel Monsif, Mahrous El Behiery and others. During our interviews of the first three days, there was a name that we kept hearing several times: Antar Shadouf. We went on with our work, but his name kept being repeated and we decided to trace that name. From our first three working days, we were already overwhelmed by the huge amount of the data we gathered and started to analyzed to the degree that the first outcome of our history project began to be in shape.

Tuesday 18 October was one of the major highlights of our field visits when we went to Ezbet El Saaida to finally meet rais Antar Shadouf. Our words cannot describe how it was to see in real life the retired rais, the person we saw only in photos as a young man working with missions in Saqqara and thought impossible to see in person. Listening to him while he was telling us about his old days as a rais with his eyes sparkling going through his memories with his colleagues, workmen and directors was very touching.

That visit wasn’t the only visit we had; other house visits were also conducted to complement the gathering of our project data. Our work wouldn’t have been completed without the help of the workmen and foremen who proudly shared with us their work achievements, education and different moments of their life.

We feel huge appreciation for all those workmen who gave us some of their time, welcomed us in their homes and showed us parts of their soul sharing their memories – both good and bad – with us.

Movie

By Servaas Neijens

One of the main outcome products of the research undertaken by Fatma and Ashraquet is a short movie about the workmen, which we will present at different venues, starting March 2023. We aim to truthfully portray the lives and work of the men by means of interviews, live footage of the dig in Saqqara and by introducing historical documents about their heritage. Oral history plays a large part in their tradition and luckily we could speak with some of the great raises and record their memories. Some of them will appear in the movies and tell their stories, while we will also show how the work of the modern workmen and Rais have developed.

On a personal note I would like to say that I have discovered how wonderful it is to listen to the Arabic language. I have been to Egypt several times, but I have always shied away from learning the language. This may change. This past week I have been interviewing the workmen and the raises with Fatma and Ashraquet, and I have come to appreciate its tone and melody very much. Fortunately, they also act as interpreters, so I can concentrate on filming while they do all the talking. I could not make this film without them!

They also make sure that the perspective of the film remains true to the Egyptian culture. This is something that we, the history team, and the people from the Leiden-Turin Mission find very important. We have almost finished filming and will soon start editing. We hope that you will all be able to see the film at some time and place next year. For now, I would like to thank Ashraquet and Fatma for their wonderful cooperation, and all the workmen for allowing them to be part of their lives and work.

This project was kindly co-funded by a generous grant of the impactfonds of the Faculty of Humanities, Leiden University.

Digging diary

Week 6 (14-21 October 2022): new colleagues, new project

By Tomasz Herbich

My name is Tomasz Herbich, I specialize in non-invasive archeology, i.e. I try to find archaeological structures invisible on the surface in a way other than through excavations. For this purpose, I use geophysical methods. I already worked in Egypt in the 1980s. I have been working in Egypt every year since the end of the 90s. Until now, I have conducted research on over 100 sites, both in the Nile valley and in the Delta, in oases, and on the shores of the Mediterranean and Red Sea. I work at the Institute of Archeology and Ethnology of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw.

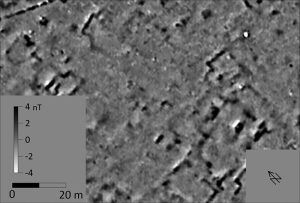

In Saqqara, I conduct research using the magnetic method. I am accompanied by Mr. Konrad Jurkowski, a graduate of archeology at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow. The method is based on the observation of changes in the intensity of the Earth’s magnetic field and allows you to register objects that create their own magnetic field, located no deeper than 1-2 m. The magnetic method has been successfully used in Egypt for nearly 50 years. Initially, it was a very labor-intensive method – by taking measurements in a sampling grid of a density one measurement per one square meter, it was possible to examine an area of 1000 m2 during the day. Since the end of the 1980s, after the introduction of instruments with a short measurement time and automatic recording of the data in the memory of the instrument, the survey can cover an area ten times larger during the day, with a much denser measuring grid (8 measurements per square meter).

The effectiveness of the method is due to the fact that the basic building material throughout the history of Egypt was sun-dried brick, made of Nile silt. Nile silt contains iron oxides, which causes that the magnetic value of mud brick walls is usually different from the surroundings. The magnetic method also allows you to register objects such as kilns and hearths, clusters of ceramics, walls made of burnt bricks.

Starting the geophysical prospection in the New Kingdom necropolis in Saqqara, we are involved in a series of research conducted in the Saqqara area since the mid-1970s. The research was initiated by the Czech mission with magnetic and electrical resistivity measurements in Abusir. The research led to the finding of a complex of tombs from the Late Period. In the 1980s, the research was conducted by the Polish mission. It led to the discovery of graves from the Old Kingdom to the Late Period. The largest survey in terms of area was carried out by the Scottish mission, led by Ian Mathieson. As a result, the limits of areas with tombs in the area from southern Abusir to the area of the New Kingdom necropolises were estimated. Last year, the Czech mission resumed geophysical research. As a result, a detailed plan of the necropolis was obtained, lying along the border of the desert and the Nile valley, at the base of the desert plateau.

Measurements using the magnetic method require a lot of effort – the person carrying the instrument (Konrad Jurkowski) walks a distance of 10 to 15 km a day. Traverses are marked on the surface with tapes and lines (each measurement must have precisely defined coordinates in the x and y axes). The effort put into the measurements is rewarded with the moment when – after transmitting the measurements to the computer – we see a map showing structures invisible on the surface.

Magnetic map. Dynamics -/+ 4 nT (white/black). Sampling grid 0.25 x 0.5 m. Image: Tomasz Herbich.

The aim of our research is to discover the boundaries of the necropolis and, if possible, its plan. We also want a more detailed picture of the part of the necropolis investigated by the Mathieson mission.

Digging diary

Week 5 (7-14 October 2022): a family affair

By Lyla Pinch Brock

Hello, my name is Lyla Pinch Brock. I am a senior member of the team here at Saqqara; I have been on site for almost twenty years. I am a jack-of-all-trades archaeologist and have worked in Turkey, Yemen, Crete and mainland Greece as well as Egypt. Most recently I directed the restoration of the pink granite sarcophagus lid of queen Takhat in KV 10 and recorded the extensive decoration.

I specialise in drawing whatever comes up during an excavation. The Leiden-Expedition to Saqqara appreciates having drawings of our finds as well as photographs because each one provides different information about the object. I work closely with our photographer, Nicola Dell’Aquila and our photogrammetry specialists, Alessandro Mandelli and Andrea Pasqui. While us seniors cannot leap gazelle-like around the excavation like the other younger team members, we do bring experience that can be valuable in terms of knowing what should or can be done in certain field situations.

We are having a catch-up season because we have missed so many due to the Covid crisis. Many granting agencies, like the Friends of Saqqara, have helped us put this season together. Normally we work in the late winter to early spring but this time we are dealing with the sometimes penetrating heat of September and October. There is a large crew here and MEHEN has kindly helped us with a grant to accommodate us outside of the full dig house for a week.

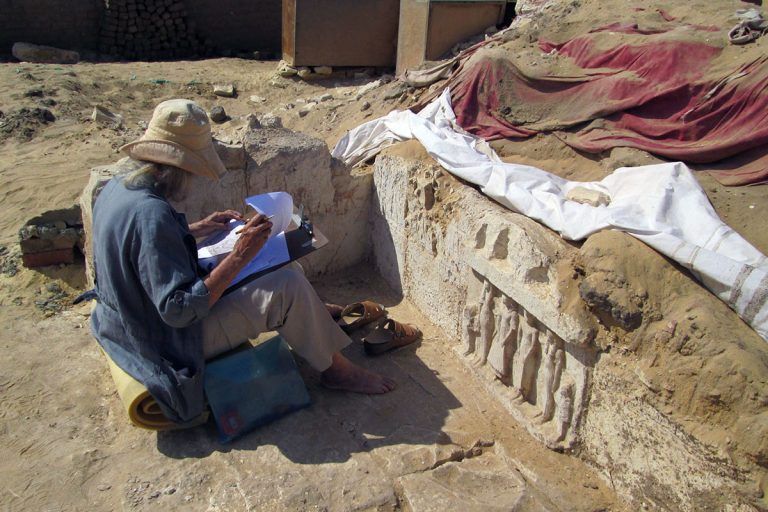

I am wearing two hats this time – helping our ceramics specialist Barbara Aston prepare the pottery plates for the forthcoming publication by Maarten Raven, Five Tombs – and thanks to a grant from The Amarna Foundation, I am doing detailed illustrations and architectural drawings of a wonderful Chapel that we found on our site in 2019.

The owner of the Chapel is unknown. The building is made of poor-quality limestone and is attached to a larger structure. It has three walls and probably once had two pillars; only the bases of these remain. It would have been a place for visitors to leave offerings for the deceased.

Although it is small, only about two meters by three, the Chapel is very special because in the center of the back wall, at floor level, there are six figures carved in the round in extremely fine detail, almost perfectly preserved. Such decoration is normally only found on stele. The figures probably represent family members: There are two women flanking two men with their arms wrapped around their shoulders, and perhaps two children, one on each side.

The men’s costumes are different, the one on the left wears an elaborate full-length pleated garment and wig, and the one on the right is bald and wears a long kilt. Every detail is minutely carved, even down to the toe and fingernails. We asked our conservator, Madame Basma, about cleaning the dust and accumulated dirt from the reliefs and she is studying them to see what can be done. She indicates, while probing delicately with a cotton swab, that there is more colour there than is readily visible, and we are glad to hear that. To the left of the family group is some incised relief showing mourners and offering-bearers, and there is a bit of miniature cavetto cornice on the right, but whatever was once below it is now gone.

Aside from applying a hardening material to the limestone, we are considering producing a three-dimensional copy using photogrammetry. But for now, the obvious choice to protect it on site is replace the permanent covering made of sheets of plastic, plywood and fired brick with a studier structure composed of limestone blocks and mortar. Certainly, preserving this Chapel, like all of Egypt’s monuments, in a time of global warming continues to present a real challenge.

Digging diary

Week 4 (30 September-7 October 2022): detectives

By Paolo Del Vesco

Hi, I’m Paolo Del Vesco, I work as a curator and archaeologist at the Museo Egizio and I’ve been taking part in the Saqqara project since the beginning of the joint Dutch-Italian collaboration in 2015. It’s always very nice to return to Egypt and see so many friendly faces again, but this year, after the long pandemic break, even more so than ever before.

My task here is supervising the excavation activities. I joined the team in the field two weeks ago, and these have been very interesting! In the first days we continued the preparation of the excavation area already started by Daniel Soliman as soon as the mission was opened. This was a very important activity, as it allowed us to better delineate the limits of the new tomb, especially along the west and south sides, and then to safely work inside it. And there we’ve got the first surprise: the lower part of the west wall of the tomb has, at a certain point in time, apparently been razed and reused, together with another wall built parallel to it, as the base of some kind of walking surface.

After we had finished with the surroundings, we began digging inside the tomb superstructure. It is here that we expect to find the most interesting things and deposits, although sometime quite the opposite happens. Since ancient times, tombs have attracted the attention of people looking for precious materials, reusing stones for other constructions or acquiring nice artefacts and reliefs for collections of antiquities. All their activities were of course concentrated inside the tombs. As a result, archaeologists in Saqqara are confronted with much disturbed contexts and tombs that are almost completely stripped of their original decorated limestone walls.

Already in 2018 we had documented traces of plundering activities. Therefore, our expectations for finding decorated chapel walls this season were rather low. Yet as soon as we started working inside, a series of upright limestone slabs appeared. They are still standing in the same position where they were originally placed by the tomb builders, clearly marking the walls of the three western chapels of the structure. What is more: some of the blocks still preserve the bottom part of their relief decoration!

Other decorated limestone fragments have been found in the deposits filling the chapels. These were mixed with fragments of funerary objects (coffins and shabtis) and bones most likely coming from the plundering of burials. Under these complex circumstances, I’m very glad that last week Nico Staring joined the team and is now supervising the digging activities with me.

The job involves a lot of troweling, brushing, filling baskets, carrying and emptying them, photographing soil deposits and structures, labelling but, above all, brushing. Indeed one of the most important parts of the work is cleaning, cleaning and cleaning again, in order to be able to see tiny differences in color or compactness in the deposits that fill the tomb. None of this works would be possible without the help of the Egyptian specialized workforce that is hired locally and that has been working with us for years now.

We feel like detectives looking for traces that could tell us how the tomb was built and decorated, and what happened when it was abandoned and later reused, when it collapsed, when it was inevitably covered by wind-blown sand and then when it was robbed in both ancient and modern times and how it was finally covered by the dumps of the modern archaeologists. For me, the highlight of the week was without any doubt marked by the re-discovery of an old acquaintance: a large robbers’ pit dug in the middle of the tomb courtyard, probably in the 19th century, that we are tracing since 2018 and which we could now finally see in all its technical beauty, with a wonderfully built dry-stone retaining wall that allowed the diggers to reach down to the tomb shaft opening. What a great emotion for an archaeologist!

Week 6: Tomasz Herbich at Saqqara (photo: Nicola Dell’Aquila)

Week 6: Konrad works together with Maghed Rubi Assam taking measurements. (photo: Lara Weiss)

Week 5, 2022: At work on site copying the family group (photo: Barbara Aston)

Week 5: The family gets their group photo (photo: Nicola Dell’Aquila)

Week 4: Paolo working inside the tomb (Photo: Nicola Dell’Aquila)

Week 4, 2022: Assam Sayed, Paolo, Magdi Rubi, Rafa’at Eid, Mohammed Sayed and other workmen looking at one of the upright limestone slabs marking the walls of the western chapels of the tomb (Photo: Nicola Dell’Aquila)

Digging diary

Week 3 (23-30 September 2022): archeometry

By Simone Galli

Let me introduce myself: I am Simone Galli and on September the 16th, on my 30th birthday, I received as a present the opportunity to join the joint Leiden-Turin mission for the first time. In this excavation season, I am supporting the topographic and photogrammetric survey activities, aimed at studying and documenting the archaeological contexts.

Currently, I am a PhD student at the Department of Architecture, Built Environment and Construction Engineering (ABC) of the Politecnico di Milano and I deal with archaeometry, more precisely non-destructive testing. In particular, I study computed tomography – an imaging technique that uses penetrating electromagnetic waves to “look” inside objects – and its applications in the field of Egyptology. In this adventure I am supported by my colleague (and, let me say, my mentor) Alessandro Mandelli, a specialized technician from the ABC Department, in his third season here in Saqqara.

Alessandro and I represent, in this context, “the operational arm” of the EIDOLON Experimental Unit belonging to the ABCLab Laboratory System. The scientific coordination of the EIDOLON Unit is entrusted to Dr Corinna Rossi, associate professor of Egyptology at Politecnico di Milano. The aim of the Unit’s research is to identify the most efficient and effective criteria and processes to document and investigate archaeological finds and to communicate the results.

We provide the archaeological team with constant metric information during the progress of the excavation. This information is obtained by both topographic and photogrammetric means. The latter technique allows for the rapid acquisition of photographic data that are subsequently processed to produce high-precision three-dimensional models. This allows us to investigate over time what no longer exists, since archaeological excavation is by its very nature destructive.

Every morning, the mission members head to the site at 6:30 a.m.; some by car, some by foot. I prefer to walk because this way I can admire very closely the impressive Step Pyramid of Djoser. In the morning, my first activity is setting up the coordinate system for the correct positioning of archaeological finds. This first operation is carried out by means of a surveying instrument called Total Station.

We spent the first week of work to double check the excavation’s grid system. All excavation activities take place in a very organised manner within a point grid with a 5-meter interval. This makes it easier to precisely locate the position of the finds.

During my second week, after the arrival of other team members, we moved on to the three-dimensional documentation of the finds and the site. Some of this work is quite predictable, like surveying the surroundings, but other aspects are dictated by the finds of the moment, like the discovery of structures.

Every Monday and Thursday, at 1 p.m., that is, at the end of the working day at the site, we document the progress of the entire excavation area. We photograph the entire excavation site and process it, using specific software, to create both a three-dimensional model and orthophotos. Because this is done throughout the excavation, it will allow the archaeologists to “go back in time” if needed and view the site at earlier points in the excavation.

I end the week with the sad awareness that this is my second and last week. As you are reading this, I am on my way to Milan and my colleague Andrea Pasqui is going to take my place. He is a Ph.D. student at the ABC Department of Politecnico di Milano like me and is studying the dissemination of archaeological sites through photographic imaging techniques. Together with Alessandro, he will continue the measurement activities to support the excavation for the rest of the season.

Digging diary

Week 2 (16-23 September 2022): textile fragments

By Valentina Turina

After opening the site, here we finally are to get going! I am Valentina Turina, a textile restorer, and this week I was finally able to study the textiles that have been discovered during past excavation seasons.

In the campaigns of the past years, in fact, a lot of textile fragments of different sizes were collected. They are linen, the most common fabric in Ancient Egypt. In addition to linen fragments, there are also Coptic fragments characterised by colourful woollen weaves that create beautiful decorative elements. Hundreds of linen fragments are waiting to be looked at! This week, my goal was to view all the linen textiles found in the 2019 season and decide how to store and conserve it.

I started by selecting the most noteworthy textiles and taking overview photos of them. This sounds like an easy job, but on the site there are many challenges, primarily the wind. The textiles are very light and are at danger of being moved during windy desert days. So, I armed myself with patience and entomological pins and fixed the small fragments on a piece of acid free cardboard so that I could photograph them properly. With the invaluable help of our photographer, Nicola dell’Aquila, I succeeded in this task.

This first phase of work was full of surprises: there were pieces with small fringes, tunic elements, and textiles with several types of stitching. Among the latter, I was immediately captivated by a triangular-shaped fragment that, after studying its shape and edges, turned out to be a fragmentary loincloth. Among the many linen fabrics, I also found some bone elements, promptly photographed and catalogued by our team member Ali Jelene, who studies the human remains for the excavation.

A second particularly important aspect of my work is the preservation of the textiles. Indeed, it is important that the textiles be properly preserved, as much as possible sheltered from external conditions. I spent the last days of this week taking care of conservation procedures that are essential for the preservation of the finds, such as dusting, smoothing out creases, and finally, store them inside micro-perforated bags, suited for storing the finds on the site.

I end this week at the excavation by reflecting on how to continue the study of these textiles and what improvements to make to the artifact storage system.

Digging diary

Week 1 (14-16 September 2022): opening the site

By Lara Weiss and Daniel Soliman

In 2020, 2021, and spring 2022, the Leiden-Turin Excavations at Saqqara were cancelled due to the travel restrictions of the ongoing pandemic. We are therefore very happy to finally be able to continue our work this autumn. The mission will take place from 14 September to 27 October. We plan to finish excavating the small but monumental New Kingdom tomb in the area north of the tomb of Maya first uncovered in 2019, to learn more about its original owner, and of the later burials that might have reused the space. Apart from our usual aims, we have some other exciting projects lined up that will be revealed in upcoming digging diaries.

Departing from Amsterdam, the long wait at Schiphol airport on Tuesday 13 September (almost 4h!) was quite a challenge for us, but eventually we were very happy to leave towards Cairo with only a bit of a delay. Cairo greeted us with a warm breeze of almost 28 degrees at 23 PM, and we were delighted to finally see Moshir Tawfik again, our friendly driver, who has been working for the Netherlands-Flemish Institute in Cairo (NVIC) for decades already. Daniel went on to meet his family, while Lara stayed overnight at the NVIC, together with our Italian colleagues from the Museo Egizio: mission co-director Christian Greco, the mission’s photographer Nicola Dell’Aquila and Valentina Turina, textile conservator from the Museo Egizio who will study our linen finds in detail. The rest of the team will arrive on Friday, and the work shall begin on Sunday, the first day of the Islamic work week, that has Friday off.

Our first goal before excavating was to finalize all administrative matters and open the site, which means unlocking the sealed spaces we left in 2019. It is an official procedure attended by a committee of Saqqara officials of the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities (MoTA), who together with the mission directors, Christian and Lara, inspect the state of the site. The directors and the committee make plans for the upcoming season, such as hiring the workforce, setting salary rates, and decide if and where restauration is urgent.

On 14 September, in the morning we first delivered a big chunk of Dutch cheese to NVIC’s director, Rudolf de Jong, we greeted everybody in the institute, and then moved on to Giza, where we signed our contract in the MoTA office for foreign missions. Secretary-general of the Supreme Council of Antiquities of Egypt, Dr Mostafa Waziri, and the permanent committee kindly approved all our plans for this season, except for the study of the underground chambers of the 2nd Dynasty tomb underneath the tomb of Meryneith, which will be postponed until another time.

From Giza, we drove to Saqqara to see the (General) Directors of Saqqara, Dr Mohammed Yousef and Dr Sabry Farag, as well as many other Egyptian colleagues and old friends such as Salah el-Deen Hasabalaa. He helps us with the day-to-day business like the acquisition of our workforce, grocery shopping, and is also in charge or our equipment storerooms. Of course, many thing such as books, lamps, and tables cannot travel back and forth every year, and it’s great to store them away in Egypt. We also saw our usual rais (the, overseer of workmen) Mohamed Fawzy, and several other Saqqara friends such as Assam Rashed and Mohamed Ibrahim, and last but not least our housekeeper and chef of the Saqqara dighouse, Atef Sayed Ramadan, who served us a nice lunch after we had settled in and unpacked.

The next morning, on 15 September, we went up to the site around 8 AM to be reunited with the excavation area that we had to miss for so long. We were very glad that to see the tombs and a good state. Yet, it is clear that climate change is also affecting Egypt, and three seasons of heavy rainfall have caused some of our modern tomb wall restorations to begin erode. Officials from the MoTA opened the storerooms, and now the site is ready for the mission’s work. Afterwards, we visited Dr Mohammed Yousef and Dr Sabry Farag at their ongoing excavation of the Bubasteion cemetery, well-known from the recent Netflix documentary. After a very pleasant chat, we went to our dighouse to enjoy our lunch. Tomorrow, the mission’s director Lara and Christian will leave Egypt to attend to other obligations, but our colleagues Ali, Alessandro, Barbara, Lyla and Simone will arrive soon to join the team. Then, finally, on Sunday we will begin working on the site.

And of course, we will keep you updated about our findings and activities. Stay tuned!

Week 3, 2022: Survey of the excavation area

Week 3: Topographic measurements using the Total Station

Week 2: Process of making overview photos

Week 2: Pinning of textile fragments with fringes

Week 1: Signing the book to open the site

Week 1: Christian and Lara in Saqqara

Week 1: Mission accomplished: Mohammed Hendawy opens the tombs

Week 1: A tomb seal