Participation in the international UNESCO Project

During the winters of 1962-64, a team from the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden excavated a complete village from the late Meroitic period (2nd-4th Century AD) just north of the temples of Abu Simbel. The team was led by the director of the museum at the time, Adolf Klasens. However. Soon thereafter in 1964 this archaeological site disappeared under the waters of Lake Nasser. For the first time since the excavation, the finds (donated by the Egyptian government to the National Museum of Antiquities) as well as the field documentation from the archaeological mission are being extensively studied and described, in a research project first initiated in 2016.

International rescue mission

In 1954 the Egyptian government decided to build a new dam in the Nile near Aswan to supply the growing Egyptian population with enough water and electricity. A consequence of the new dam was that a large lake of about 500 km long was created to the south of Aswan. Due to the rising waters thousands of Nubians had to move. The governments of Egypt and Sudan enlisted the help of UNESCO to set up and coordinate an international project to save most of the monuments and sites.

Two archaeological sites

About 30 countries applied, including the Netherlands. An excavation team of the museum, led by Adolf Klasens was designated an area just north of the Abu Simbel’s temples. During an earlier survey carried out in the context of the aforementioned UNESCO project two archaeological sites were identified in this area: a village from the early Christian period that was later named Abdallah Nirqi and an older village from the late Meroitic period, named Shokan by the excavators after a contemporary but abandoned hamlet nearby. Both sites were already described in 1907 by the English Egyptologist Arthur Weigall.

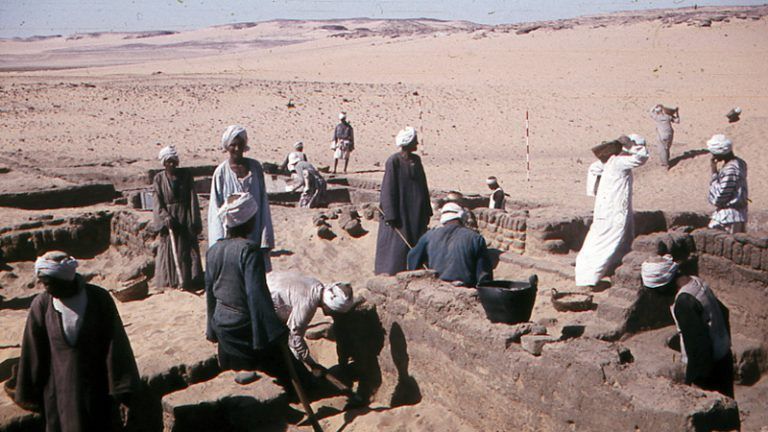

Thirty houses in Shokan

In Shokan the team excavated around 30 house structures, wherein they found various domestic artefacts including cooking pots, grindstones, weaving implements, beads, and tools. They also found numerous sherds, including the special Meroitic eggshell pottery with walls as thin as an egg shell. In 1969 the Egyptian government donated the temple of Taffeh to the Netherlands as a thank you for the rescue work and the advice of Klasens and his team, as well as the financial support of the Netherlands. The temple now stands in the entrance hall of the museum.

The Meroitic Empire

Kush is one of the old names for an area in Nubia and for the successive empires that emerged here. In the 8th century BC the Kushites temporarily conquered Egypt. Around 280 BC the centre of the Kushite Empire moved from the religious centre of Jebel Barkal near the 4th Cataract, to the southern city of Meroë between the 5th and 6th Cataract. We know this because from that time on the kings are buried at Meroë and no longer near Jebel Barkal. In the Meroitic period the area once again developed into a powerful empire and played a major role in the trade of, among others, ivory, gold and incense between Mediterranean Egypt and tropical Africa. The delicate egg shell pottery was found throughout Nubia. The people of Meroë mined iron on a large scale confirmed by the countless iron ore quarries discovered around the capital and other southern Meroitic centres. Gold was found and mined in various places and was used to create precious jewellery and religious objects.

A village almost completely excavated

To date, relatively little is known about daily life in Meroitic settlements as it is not common for villages to be excavated in their entirety. Particularly, in the last century people were more interested in cemeteries because the graves of the deceased often contained burial gifts. Apart from giving an impression of the size and the composition of the population, these objects were of much interest for exhibitions in the museums of the western world, whilst architectural ruins were considered far less important. Fortunately, this point of view has changed in recent decades. Shokan is one of the few Meroitic villages that were almost completely excavated, hence the significance of the settlement.

Purpose of the recent research

After two excavation seasons, the National Museum of Antiquities was allowed to take the largest part of the finds to the Netherlands. These finds are partly on display in the museum, but have never been studied extensively. Current research, conducted by archaeologists Liliane Mann and Ben van den Bercken is once again examining the excavation. Can we say something about the architecture and the construction of the buildings in Shokan based on the documentation and the photographs made by the excavators in the 1960s? What was the function of the village in the region? The excavation methods used during the excavation of Shokan are investigated as well. Is there anything to be said about these methods after so many years? The research also focuses on the objects found in Shokan. These are reviewed and if necessary described again. In this way we hope to learn more about the age and the use of the various objects. Taken together, it is expected that the analysis of construction, architecture, function and the history of the objects found in Shokan will ultimately provide a better picture of life on the border of the Meroitic Empire.

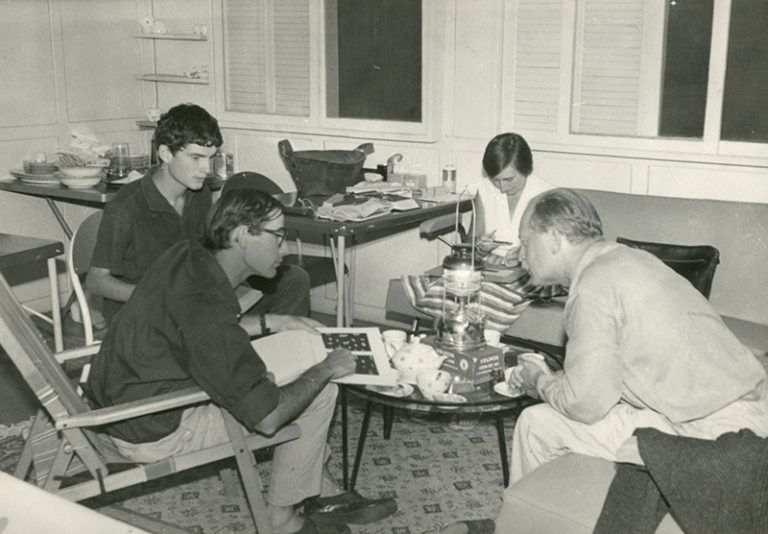

The excavation team during the second season: Servaas Wildschut, Hans Schneider, Helen Jacquet-Gordon, Adolf Klasens.

Excavations in Shokan: house B5 and B19.

News

Publication: L. Mann & B. van den Bercken (2022). Shokan: Revival of a forgotten village. In S. Tipper, S. Shin and L. Kilroe (eds.), Current Research in Nubian Archaeology. Oxford Edition (pp. 117-135). Giorgios Press LLC.

Liliane Mann gave a presentation on 5 November 2021 at the online CIPEG conference (5-7 November 2021), titled The Revival of Shokan, a Late Meroitic Village.

Publication: Mann, L.Y. & B. van den Bercken, 2020. Shokan, Revival of a forgotten village. Sudan & Nubia 24, 24-30.

The 3rd Sudan Studies Conference was held in Oxford on Saturday 4 May 2019. The conference was organized by the University of Durham, this year in collaboration with the University of Oxford. Ben van den Bercken and Liliane Mann gave a lecture about their research with the title Shokan, a Meroitic village revisited.

Liliane Mann and Ben van den Bercken in Oxford.

Bibliography

- Arnold, D. 2003. The Encyclopedia of Ancient Egyptian Architecture. London: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd.

- Adams, W.Y. 1964. Post-Pharaonic Nubia in the light of Archaeology. I, Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 50, 102-120.

- Edwards, D.N. 2004. The Nubian Past. An archaeology of the Sudan. London/New York: Routledge.

- Edwards, D.N. 1996. The Archaeology of the Meroitic State. New Perspectives on its social and political organisation. BAR 640. Oxford.

- Haelvoet, T. 2006-07. Description de L’ Egypte of een retroactief Stadsproject voor Luxor. Universiteit Gent, masterscriptie.

- Husselman, E.M. 1952. The Granaries of Karanis, in Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, Vol. 83. Boston: Johns Hopkins University Press, 56-73.

- Jacquet, J. 1971. Remarques sur l’architecture domestique à l’époque Méroitique Documents recuellis sur les fouilles d’ Ash-Shaukan, Beitrage zur Ägyptischen Bauforschung und Altertumskunde Heft 12, 121-131.

- Jacquet-Gordon, H. 2000. Les ostraca Meroïtiques de Shokan, Meroitic Newsletter 27, 31-75.

- Kirwan, L. 1963. Land of Abu Simbel, The Geographical Journal, Vol. 129, No.3, 261-273.

- Klasens, A. 1964. De Nederlandse opgravingen in Nubië. Tweede seizoen: 1963-1964, Phoenix X, no. 2, 147-150.

- Klasens, A. 1963. De Nederlandse opgravingen in Nubië. Eerste seizoen: 1962-1963, Phoenix IX, no. 2, 57 – 66.

- Leclant, J. 1965. Fouilles et travaux en Égypte et au Soudan, 1963-1964, Orientalia 34, 201-203.

- Leclant, J. 1964. Fouilles et travaux en Égypte et au Soudan, 1962-1963, Orientalia 33, 360-362.

- Moorsel, P. van, J. Jacquet, H. Schneider. 1975. The central church of Abdallah Nirqi. Leiden.

- Raven, M. 2007. Hakken in het zand, 2007, Leiden.

- Schneider, H. 1965. Het aardewerk van de Meroïtische nederzetting te Shokan bij Abu Simbel, onderzoeksverslag, archief RMO doos C 136. Leiden: n.p.

- Schneider, H. 1963-’64. Personal Field diary, n.p. Leiden-Oegstgeest.

- Shehata Adam, M., 1980. Victory in Nubia: Egypt, in: Unesco Courier 33rd year, Paris, 5-16.

- Smith, H.S. 1962. Preliminary Reports of the Egypt Exploration Society’s Nubian Survey. UNESCO’s International Campaign to save the Monuments of Nubia. General Organisation for Government Printing Offices, Cairo.

- Shokan Archieven, 1962-1964. Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Archief 1. C 134: 8.2.2b/15a-15f; C 135:z.t. 8.2.2/16c, 8.2.216h, 8.2.2/16j; C 136: 8.2.2/17d-f, 8.2.2/18, 8.2.2/19; C136a: 8.2.2/g-h; BNR 1:1740-1748.

- Török, L. 1997. Meroe city. An ancient African capital. John Garstang’s excavations in the Sudan. London.

- Weigall, A.E.P.B., 1907. A Report on the Antiquities of Lower Nubia (the first Cataract to the Sudan frontier) and their condition in 1906-7. Oxford: University Press.