The research team sends a Sakkara diary of the excavation every Tuesday

(see below photos)

Excavation campaign 2023

On 19 February 2023, the international research team came together in Saqqara to work on this Egyptian site until 24 March. For nearly fifty years, the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden has been conducting excavations in Saqqara, the cemetery of the ancient Egyptian city of Memphis. As of 2015, the museum collaborates in this project with the Museo Egizio in Turin.

- Read more about the backgound and history of the excavation project in Saqqara

Continuation after delay

After two and a half years of delay, due to the corona pandemic, the Leiden-Turin excavations finally resumed in the autumn of 2022. That season, the team excavated the monumental tomb of Panehsy. He was a dignitary in the reign of Ramesses II (c. 1279–1259 BC).

Tomb of Panehsy

The investigation continues this year in and around the tomb to find out more about Panehsy and the area where his tomb was built. In addition, previously excavated objects will be studied, such as fragments of wooden statuettes and coffins. You can read about this work and much more in the Saqqara diaries, which will appear weekly.

- Read the Saqqara diary

- Read the Saqqara diary week 4

- Read the Saqqara diary week 3

- Read the Saqqara diary week 2

- Read the Saqqara diary week 1

Partner Museo Egizio

The team consists of several scientists and is led by Dr. habil. Lara Weiss and Dr. Daniel Soliman (curators of the Egyptian and Nubian collection of the National Museum of Antiquities), together with Dr. Christian Greco, director of the Museo Egizio, Turin. The project is co-funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research and the Friends of Saqqara Foundation.

Week 5: Basma Zaghloul at work restoring the stela of Panehsy. (Fig. 1)

Week 5: Christian Greco and Lara Weiss reading the texts in the new tomb chapel. (Fig. 2)

Saqqara diary

Week 5 (28 March 2023): Living Memories at Saqqara

By Christian Greco and Lara Weiss

When you are reading this, we will have finished our work and closed the site on Wednesday 22 March, just before the start of the feasting month of Ramadan, to take into account the fact that the physical work at the site would be very hard on our fasting Egyptian colleagues. We will have had our farewell team dinner, the international team will have scatters into various directions again, and will be home again in the hopefully not so cold weather and back at our desks finalizing our forthcoming field report publication. And our Egyptian workmen will be back home, too, working their ‘normal’ jobs as farmers, drivers or electricians.

We had a great season together, with again a wonderful team spirit among the Egyptian-international team and very good results.

We did not only manage to finish the excavation work on the tomb of Panehsy, which – thanks to a generous grant by the FRIENDS OF SAQQARA and the work of our Egyptian restorers Basma Zaghloul and Yousef Hammadi – received a decent restauration this season (Fig. 1), but we also discovered that his tomb was about a century after his death, reused by a High Priest of the goddess Hathor, Mistress of the Sycomore, called Pinodjem, who might have lived in the 21st dynasty, and we found a new chapel (Fig. 2).

This season was also interesting in terms of visitors: we had several important encounters: our Leiden Head of Finances Guus Waals visited, and of course also inspected the results of the EU project that worked with the Egyptian colleagues to redesign some galleries in the Egyptian Museum, where he also saw Willem Pleyte, the former director of the RMO in the 19th century, whose bust stands in the garden of the Egyptian Museum. And on occasion of Guus’ visit, His Excellency the Dutch ambassador kindly invited us and several Egyptian colleagues for a nice dinner in his residence, where we met and chatted about our current and future cooperations. And there were more honorary visitors: His Excellency, the Italian ambassador and his wife marvelled at ‘our’ Saqqara tombs at a private tour with Christian.

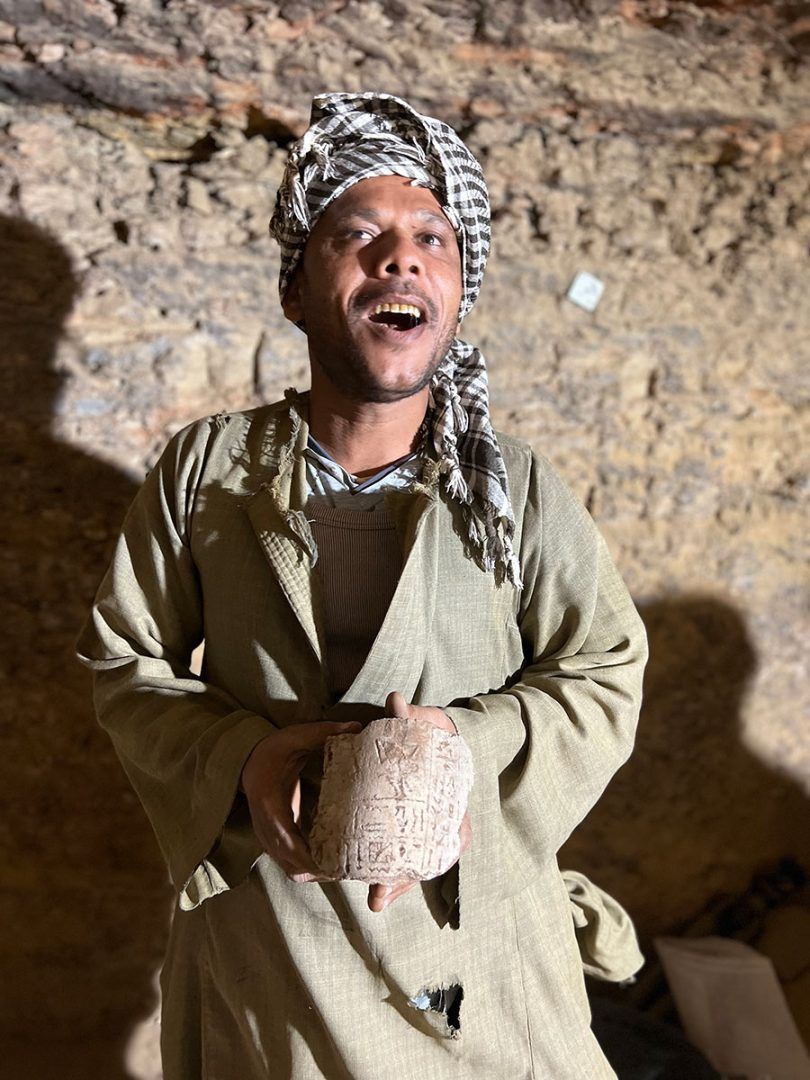

This season we had our very first field trip together with some of our Egyptian colleagues. We hired a bus and went to Cairo to celebrate the first public screening of the film ‘Living memories: The workmen of Saqqara’ at the NVIC, that was made possible thanks to the great organisation of our colleague Fatma Keshk and the hospitality of the institute’s director Rudolf de Jong, we could end that wonderful night with drinks on the roof terrace! 𝐋𝐢𝐯𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐌𝐞𝐦𝐨𝐫𝐢𝐞𝐬: 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐖𝐨𝐫𝐤𝐦𝐞𝐧 𝐨𝐟 𝐒𝐚𝐪𝐪𝐚𝐫𝐚 is a short film by the Leiden-Turin Expedition to Saqqara that was made by: Fatma, Ashraquet Bastawrous and Servaas Neijens and presents the memories of some of the workmen being involved in 50 years of the Leiden-Turin Expedition to in Saqqara (Fig. 3). Instead of taking our own perspective as usual, we had the aim to document and indeed value the vital contribution of a major group of these professionals and to link their work to their historical legacy since the late 19th century. In the film our Egyptian colleagues speak about their work as technical workmen, foremen, restoration workmen and also about their passion to excavate, their inheritance of the profession and about their daily routine on the site and how they experienced the work with us and our predecessors.

An excavation site is a workplace, but it is also it is greater than that. We make friends with ‘our workmen’ and they make friends with us, and among themselves, if they are not already linked by family relations. The close ties between the workmen are clearly seen in their friendship inside and outside the archaeological site. The fact that they all live in Saqqara or in its close surroundings creates through time professional but also social bonds. Workmen are relatives, neighbours and friends before becoming workmates, and they become our workmates and friends for generations. Therefore ‘our’ site feels like a second home where we have been working together for most or all of our professional lives. Therefore, the end of this season fits also a Dutch saying well, namely that we are leaving with a laughing and a crying eye. Why? Because this was our last season together as field directors (Fig. 4) because Lara will take up her new position as managing director of the Roemer- und Pelizaeus Museum in Hildesheim (Germany) by the 1st of May and is hence leaving not only the Leiden Museum, but also her position as co-field director of the Leiden-Turin Expedition to Saqqara. Good luck Lara and thank you for all you have done! We will be waiting for your visits, you are the soul of this project. But no worries! Other great colleagues are already lined up to take over. The RMO is in the middle of the selection procedure of the new curator as we speak. Exciting times for everybody. Living memories also for us. So stay tuned.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to acknowledge and express our gratitude and appreciation to all Egyptian and international team members, the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, with special thanks to Dr Nashwa Gaber and Dr Mohammed Youssef; the Dutch Research Council, the Impact funds of the Faculty of Humanities, Leiden University, the two Museums, the Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy and the National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden, The Netherlands.

We hope to show the film soon in Leiden and Turin.

Week 5: Assam Sayed Ahmed Taha and Rafa’at ‘Eid ‘Abdel Karim Morsi el-Kis in the tomb of Maya. (Fig. 3)

Week 5: Christian Greco, Lara Weiss, and Salah Hassaballah ready to pay the workmen their well-deserved weekly salary. (Fig. 4)

Week 4: Ready for the descent down the burial shaft of Panehsy with the tambura (photo Servaas Neijens)

Week 4: Mohammed Sayed Ragab with a fragment of a canopic vase (Nico Staring)

Saqqara diary

Week 4 (21 – 28 March 2023): Excavating underground

By Nico Staring

The excavation campaign of 2023 is largely dedicated to the subterranean complex of Panehsy. The monumental tomb superstructure was excavated in 2022, and during the first half of the present season the area due east of the tomb was explored. The latter was carried out under the supervision of Paolo Del Vesco. We divide our tasks this year and so I relieved him of his work halfway through the season. My name is Nico Staring and since a few years I play the part of the expedition’s archaeologist. I am mainly interested in the development of the landscape of Saqqara during the New Kingdom (c. 1539–1078 BCE). Core questions pertain to the choices underlying tomb location, accessibility and clustering of tombs. My current research project at the University of Liège focuses on the relationship between tomb owners and the makers of their tombs. The study revolves around the tomb reliefs that represent the end product of the cooperation between commissioning patron and artists. Without giving away too much about this year’s excavation campaign, I can say that both these interests have been served well!

Now back to the tomb of Panehsy. Part of the underground complex had already been excavated in 2022. The tomb shaft connects the superstructure with the subterranean spaces. Excavating that shaft had been a labour-intensive undertaking, because the bottom of the shaft was reached at no less than 11 metres under the tomb’s floor! The first metres were no cause for problems. However, the deeper the shaft, the more difficult it gets to discharge the sand. At that point it is time for the tambura, a large wooden lifting device consisting of a rope winding around a horizontal rotating drum. Iron hooks attached to the rope lift the baskets filled with sand. Above ground, the baskets are passed on by a human chain transporting all sand to the spoil heaps at the edge of the excavation area. The tambura does not just serve to haul up baskets of sand. It also serves as an elevator to lower ourselves into the deep and to get back up at the end of the work day. Also very importantly: halfway during the morning it lowers a pot of tea for the well-deserved break.

The underground complex of Panehsy consists of several spaces. For example, a small room entered from the bottom of the shaft gives access to a second shaft measuring 5 metres deep. It thus leads to the burial chamber located at a depth of 16 metres under the tomb’s floor. We were not first to travel the long distance toward the burial chamber. Ancient visitors had already taken assorted items and as a result little remained of the original burial equipment. Nevertheless, the archaeological remains help us to paint an image of what has happened there since the earliest burials more than 3,000 years ago.

During the last week, we focused our attention on a room situated at a higher level (Chamber A), accessed at 5 metres down the shaft. The space has been cut from the bedrock and measures roughly 3 by 4 metres square. It is some 2 metres high and it was almost completely filled with sand. It meant that we had to enter the room flat on our bellies and explore the space while crawling. Excavating underground is not something for the claustrophobic! All sand needs to be removed in baskets. This sort of excavation work is not a matter of speed. As an archaeologist, one tries to understand how such a space got filled with the various deposits, and what human activities led to the present-day situation. Therefore, all deposits are meticulously documented and finds such as pottery, bone material and objects are labelled and sent to the different specialists of the expedition. They analyse the finds in further depth.

The presence of a second shaft that had been cut through the ceiling of Chamber A long ago, led to some complications. While emptying the chamber it also got filled with more sand coming from the second shaft. Such as breakthrough not just slows down the work, it can lead to dangerous situations also. In order to tackle this problem a work plan was drafted in close consultation with the foreman of the workmen, rais Hossam Azzam. It is important that work underground can be done safely, and thanks to his experience of many years, Hossam knows very well how to proceed. It goes to show that excavating at Saqqara is all about teamwork. The archaeological fieldwork is largely carried out in close cooperation with a team of local Egyptian specialists and workmen. In the small underground spaces I work together with Mohammed Sayed Ragab, Rafa’at ‘Eid Abdel Karim en Walid Khaled, who have been part of the Leiden-Turin expedition for many years now. At the same time, rais Hossam directs the team aboveground.

After a little more than one week of work, Chamber A has been largely emptied. A preliminary study of the complex stratigraphy (the layering of the various deposits) already tells the fascinating story of the human activities that have taken place in this underground structure. That study will be continued back home in the Netherlands . With the help of all descriptions, photos and 3D models, we are able to thoroughly review the excavation and try to squeeze out as much information as possible from the archaeological remains.

Saqqara diary

Week 3 (14 – 21 March 2023): Topographic and photogrammetry survey

By Andrea Pasqui

Hello everyone! I am Andrea Pasqui, PhD student in Egyptology at Politecnico di Milano at the Department of Architecture, Built Environment and Construction Engineering. Here in Saqqara, I work alongside Alessandro Mandelli, a specialised technician from the same Department, on the activities of ultra-high precision topographic and photogrammetric surveying, under the scientific direction of Professor Corinna Rossi.

These survey methods, which are becoming increasingly popular in archaeological excavations, will occupy a role of growing importance, given its many applications: a three-dimensional model obtained from a photogrammetric survey, in fact, has a wide-ranging potential. Various investigations can be conducted on it: in the case of buildings, their architectural forms can be studied in order to understand the appearance and function they must have had at the time of their construction and later (re)use. On the basis of the photogrammetric survey of the tomb of Meryneith carried out by Alessandro Mandelli a few years ago, for example, I was able to model what the tomb’s original appearance might have been by referring to similar cases and the relevant scientific literature.

The possibility to freely navigate within the three-dimensional model allows one to delve into the relationships it had with the surroundings and the surrounding buildings, highlighting any alignments with other features that might missed ‘live’ on the field. And again, by superimposing different surveys made in different days, one can analyse the evolution of the excavation over time; or one can virtually eliminate disturbing elements such as modern additions that hamper an integral reading of the site. One of the most important products of our work, in addition to the three-dimensional models whose peculiarities we have already highlighted, are the orthophotos. These elaborations basically consist of the (perfectly orthogonal) projections of everything we survey on a horizontal plane: this high-resolution image (we work at a resolution in which one pixel corresponds to a tenth of millimetre) is the basis for the two-dimensional redrawing of plans of archaeological sites.

But the product of photogrammetric surveys is not just for scholars: its appeal makes it a perfect medium for the dissemination of archaeological knowledge. Indeed, three-dimensional models allow to easily explain how a tomb must have (or rather ‘could have’) looked like during the New Kingdom, for example, as well as to virtually re-insert artefacts, now preserved in museums around the world, in their original context. Some fragments of reliefs have been found during excavations in the last few days, and in the event that they cannot be physically repositioned in their original location, there is nothing to prevent them from doing so in the digital environment! In short, photogrammetric surveying has a great potential and many interesting applications, both in the academic and museum fields!

But in practice, what do Alessandro and I do?

Our day begins with the installation of the total station (photo 1): this instrument, the basis of topography, is of paramount importance for our work. In fact, it allows us to measure distances and angles with absolute precision from a previously established topographic point of known coordinates, on which we position the station. The one we use, for example, was acquired in 2019 and is called SAK19P1. Thanks to this, and the use of coded markers that we strategically place around what we must record, every photogrammetric survey we carry out will have precise and unambiguous geographical coordinates.

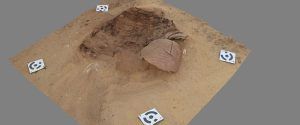

Once the stationing is complete, we can proceed with the actual surveys: we are at the disposal of archaeologists or anyone who needs to create a three-dimensional model of contexts, features or objects. If, during the excavation, a cachette of pottery or human remains or a particular object is found, we proceed with georeferencing its position in the context and then with the actual photogrammetric record: with a digital camera and wide-angle or semi-wide-angle lenses (but sometimes we even have to use fish-eye lenses, if we are working in very narrow spaces!) we take photographs of the object from all angles (photo 2). We then import the topographical data obtained with the total station and the photographs taken and process them into a highly accurate three-dimensional model. We do this several times a day, both for small to medium-sized objects (such as a decorated stele:

and for entire contexts:

as well as for the entire excavation area:

Now I must say goodbye because Alessandro is calling me to order. I’ll get back to holding the camera to tackle new surveys and produce three-dimensional models. Stay here for updates from the other team members see you soon. Bye!

Week 3: Alessandro measuring with the total station (photo 1)

Week 3: Andrea acquiring images for the photogrammetric elaborations (photo 2)

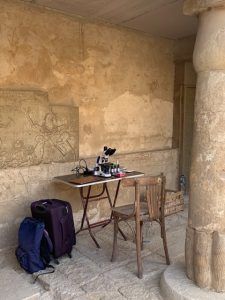

Week 2: Dr. Caroline Arbuckle MacLeod analyzes wooden objects with her microscope in the tomb of Horemheb.

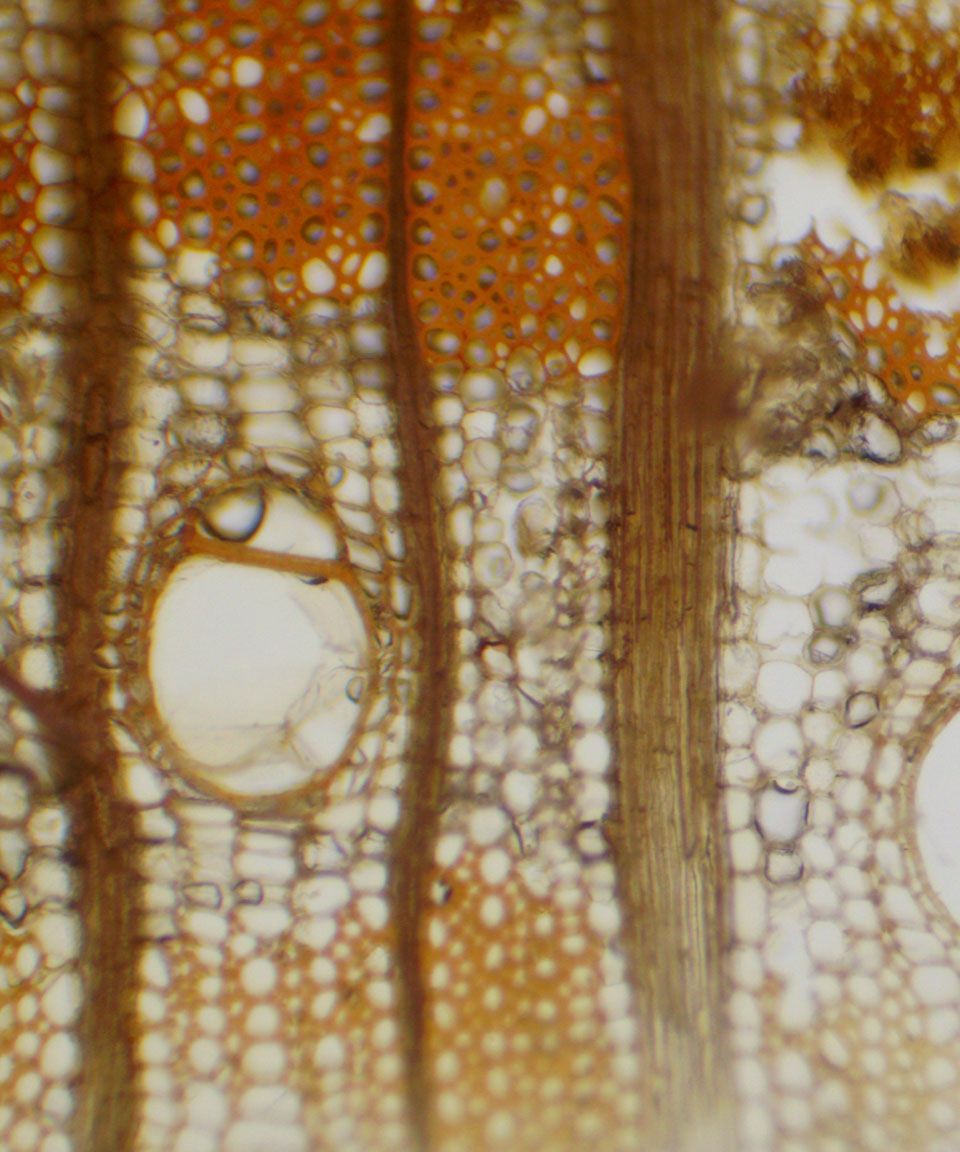

Week 2: Wood sample (sycamore fig) from the coffin under the microscope.

Saqqara diary

Week 2 (7 – 14 March 2023): In Amongst the Coffin Wood

By Caroline Arbuckle MacLeod

During the 1999 season at Saqqara, the excavators found two wooden coffins near the tomb of Horemheb. These coffins were not in great shape – the damage caused by a combination of moisture, age, and termites had left many pieces more closely resembling slices of Swiss cheese than the sturdy wooden coffins in which their owners had received their final rites.

Parts of the rectangular and anthropoid coffins found in 1999 and restudied in 2023.

They were therefore not exactly what you might consider, “museum quality”. After they were studied and published, they were therefore not put on display but laid in a storehouse in Saqqara near their original resting place. There they slept until this year, 2023, when they were awakened once more so that we might learn new information about Egypt’s ancient past.

I am Dr. Caroline Arbuckle MacLeod. I am an archaeologist that specializes in the analysis of ancient wooden objects – and I’m particularly obsessed with Egyptian wooden coffins. One of the goals of the excavation season this year was to complete a more thorough analysis of the pieces of these coffins before turning to a study of the wooden remains from more recent excavation seasons.

As we took the pieces out of the storeroom, the poor preservation discussed in the original publication was immediately obvious – and some additional critters had established their homes in the tunnels and holes left by their insect predecessors.

A spider has made its home in the coffin wood.

But it is this fragmentary, dare I say, “shabby” state, that allows these pieces to reveal information that their more pristine coffin counterparts conceal beneath perfect layers of plaster and delicate gold leaf. In this state, it is possible to take small wooden samples from multiple areas of the coffin, peer into the coffin joints, and document the tool marks that are usually invisible on a complete object. This helps us to understand what materials were used for coffin construction and provides a glimpse into the movements and choices of carpenters whose stories are otherwise so often lost and overlooked in favour of the history of kings and conquerors.

To identify the species of wood used for each object, I make thin sections of the wood samples and examine the wood anatomy under a microscope. Each tree has a unique profile and looks pretty spectacular up close!

A microscopic image of one of the wood samples from the coffin – it is sycomore fig!

When working in the field, I set up a mini laboratory for my analysis. This season I was lucky enough to be working from the tomb of Horemheb, surrounded by some of the most beautiful reliefs I have ever seen.

The field laboratory in the tomb of Horemheb.

I analyzed many of the coffin pieces as well as the tenons and dowels – pieces of wood that are used to hold the different parts in place. Ultimately, I found that all the larger parts of both coffins were made of sycomore fig, while the dowels and tenons were made of either acacia or tamarisk. This assortment of woods tells us that the carpenters selected from trees that grew locally. They picked sycomore fig because it is easy to work and grows big enough for coffin planks – and has a special religious significance connected to the goddess Nut. They joined the pieces with woods that are harder and better for holding everything in place – they knew their craft, and selected their woods carefully.

Next I looked for evidence of tool marks. Tool marks are incredible because they represent movements, frozen in time. They can connect us to the craftspeople who built these objects more than 3000 years ago! Take a look, for example, at just the foot of this coffin.

The foot of the anthropoid coffin.

Or rather, take a look at the back – the part that would usually be covered up by additional pieces of wood and paint.

The back of the foot of the anthropoid coffin. The blue lines highlight the saw marks, the orange arrow indicates chisel marks.

Across the back, we can see saw and chisel marks, the first rough cuts used for the initial shaping of this piece. Then the carpenters drew red lines to mark out where they would cut the dovetail joint that would hold the pieces of wood together – but later they made a correction and cut it smaller, leaving a faint red line behind on the wood, parallel to the final cut (an ancient instance of measure twice, cut once!).

The back of the foot of the anthropoid coffin. The red arrow points to the red paint guide line. The green arrow points to the chisel marks in the dovetail joint.

To cut the joint, they started with saws, and a tiny knick at the top shows that they cut just a tiny bit too far, but no matter, that would be covered up later.

A knick at the top of the cut shows where the carpenters sawed slightly too far.

They then took chisels to remove the last bit of wood at the back of the joint, since their saws would not fit in this space. These final rough chisel marks are left unfinished, again destined to be covered up by later construction steps. All these choices and movements are visible to us today only because time and termites ultimately undid the carpenters’ hard work. While these coffins may not seem beautiful in their rough and crumbling state, to me they are perfect reminders of the non-royal Egyptian people who left their marks on history in amongst the coffin wood.

Saqqara diary

Week 1 (28 February – 7 March 2023): A Relief for Us All

By Lyla Pinch Brock

The weather is cool in the morning out here in the desert. We are working in the shadow of the step pyramid, sombre under a sky of cotton-batten clouds. Unlike our Egyptian colleagues, the team members who flew in are not usually here in February, so they are bundled up against the cold in scarves and down jackets. We slap our hands against our sides to keep warm. But in no time at all, we are peeling off our layers and warming ourselves in the sun like lizards.

My name is Lyla Pinch Brock, and I am wearing my epigrapher hat for the next two weeks — that is, I will be a copyist. I am one of the senior team members, having been with the crew for almost twenty years. One of our jobs this season is to record the series of reliefs we found last season lining the walls of a chapel in the tomb of Panehsy. I say ‘our’ because it’s decidedly a group effort.

First on the scene is one of our dig directors, Daniel Soliman, whose main job is to expedite our work. He organises a table and chair for me and then gets two of the workmen, ‘Assam Sayed and Rafa’at ‘Eid to carefully remove the wooden hoarding and soft styrofoam we installed over the carved stones last year to protect them from the wind and rain. What with world weather patterns changing, we don’t know what to expect. Our inspector, Hanna Donqol is on hand to check the stones’ condition and take some photos.

The hoarding is carefully lifted away. We breathe a collective sigh of relief to see everything is still in good condition. However, there is some minor spalling of the stone and we all agree that some conservation is in order. Thankfully, the Friends of Saqqara foundation has offered to fund it.

The reliefs show offerings being brought before the tomb-owner, including a hapless bull so fat that his hooves have splayed under his weight. In the retinue are priests and officials rendered in small scale, while on either side of a doorway Panehsy the owner is depicted full-size, majestically accepting his due. He wears fine sandals and a pink pleated robe and holds two staves of office. He held the important post of steward of the temple of Amun during the first part of the reign of Ramesses II, around 1279-1259 BC.

I get to work. I will trace the reliefs using the excellent photographs taken by Nicola Dell’Aquila, and then collate my drawings against the walls. Once they are all checked, they will be inked in for publication. Two days later I am happy to see our conservators arrive – Basma Zaghloul Esmael and Yousef Hamadi ‘Awad, who did such a superb job last year cleaning and conserving our tiny ‘family’ chapel with its exquisite miniature statues that I had the pleasure of recording with funding from the Amarna Foundation.

This season we will also work on a large, highly-detailed and very important stela of the tomb owner which is part of the larger chapel. It was found last year on the last day of work, confirming the archaeologists’ truism: the best thing is always found on the last day.

Week 1: Lyla Pinch Brock working in the tomb of Panehsy (foto: Nicola Dell'Aquila)

Week 1: Stela in the tomb of Panehsy (photo: Nicola Dell'Aquila)